A few years back I picked up a really interesting book, Mystics, Mavericks and Merrymakers: An Intimate Journey among Hasidic Girls by Stephanie Wellen Levine. Essentially the published version of an academic thesis, Levine spent a year living among the young Hasidic girls of the Lubavitcher community in New York.

I grew up in a liberal Jewish family, in an era when women were being told they could do anything, be anything. I came to the book thinking I would believe these girls were brainwashed, restrained, shackled by a joyless life of perpetual pregnancy and servitude. They would be convinced that for two weeks of every month they were dirty, too polluted to even touch a man or serve him food. They would be forced into early marriage, prevented from realizing their creative and intellectual potential, and kept from all the art, literature, music, technology, and life of the modern world.

I grew up in a liberal Jewish family, in an era when women were being told they could do anything, be anything. I came to the book thinking I would believe these girls were brainwashed, restrained, shackled by a joyless life of perpetual pregnancy and servitude. They would be convinced that for two weeks of every month they were dirty, too polluted to even touch a man or serve him food. They would be forced into early marriage, prevented from realizing their creative and intellectual potential, and kept from all the art, literature, music, technology, and life of the modern world.

But as I read the book, I changed my mind. For a large number of these girls, their life is full of joy. They are able to move through their schooling and adolescence without having to worry about whether getting a question right will make a boy feel bad. They can be good at math and shout out answers in language classes. They don’t have to worry if their hair is right, a pimple is on their nose, or whether they should shave or wax their legs. They are innocent of everything — often including how babies are made. That part of their education comes only after they are betrothed, when they go to Kallah (bride) school. Their lives are restricted, but most of them don’t mind. They can have some career goals — helping a husband or family with a business, teaching other Hasidic girls, some even become nurses or doctors by going to one of the very few colleges approved by the community. But most long only to become wives and mothers.

In some ways, I was jealous of the way these girls get to be so free of the teenage angst I had as I grew up, the constant worry about boys and who liked me. Finding a match is out of their hands and securing a husband has relatively little to do with the girls themselves. If they are good daughters from good families, they will be married early. And the girls have a sisterhood as close as I had with my two or three best friends, but they have it with dozens of others.

Who loses are those mavericks of the title: those girls who are outliers, who want more than the small world offered to girls by the Lubavitchers. Lesbians, curious readers, technology geeks, artists, poets, writers, even strong assertive women — there is no place for them in that world. So many choose to leave it. For some, leaving means never seeing family or having the close bond of sisterhood again. For others, contact remains, but is strained.

The outliers are a minority. And while you could argue that with access to information there would be many more outliers, the reality is they don’t usually get the knowledge that would change their minds. And so most of them are happy in the little lives they have. I came away from that book a little envious, still curious, and mostly not feeling a need to go rescue the entire population of Hasidic girls.

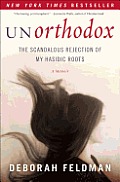

Last week, I picked up another book from the large pile next to my bed. This one: Unorthodox: The Scandalous Rejection of My Hasidic Roots by Deborah Feldman. Part of the extremely religious Satmar Hasidic community in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn, Feldman was raised by her paternal grandparents after her mother abandoned the faith — Feldman was never told the real reason why — and her father was deemed incapable of taking care of her. She always had an urge to read and hid secular English language library books the way PMSing women hide chocolate. Married off at 17, she was completely ignorant of the mechanics of sex, even of how her own body worked. She had a baby at 19 and after moving away from the heart of the community with her husband, began breaking away from the sect. She skipped trips to the ritual bath (mikve). Lying about her motives and chosen courses, she enrolled in a poetry class at Sarah Lawrence — changing into pants once she arrived at school and indulging in non-Kosher food. Eventually, Feldman left her husband. But it’s not that simple. Most women with children who leave are forced to give up custody of their kids and see them rarely, if at all. It’s what happened when Feldman’s own mother left and why she barely knew the woman who bore her before she left the Satmar community herself.

Last week, I picked up another book from the large pile next to my bed. This one: Unorthodox: The Scandalous Rejection of My Hasidic Roots by Deborah Feldman. Part of the extremely religious Satmar Hasidic community in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn, Feldman was raised by her paternal grandparents after her mother abandoned the faith — Feldman was never told the real reason why — and her father was deemed incapable of taking care of her. She always had an urge to read and hid secular English language library books the way PMSing women hide chocolate. Married off at 17, she was completely ignorant of the mechanics of sex, even of how her own body worked. She had a baby at 19 and after moving away from the heart of the community with her husband, began breaking away from the sect. She skipped trips to the ritual bath (mikve). Lying about her motives and chosen courses, she enrolled in a poetry class at Sarah Lawrence — changing into pants once she arrived at school and indulging in non-Kosher food. Eventually, Feldman left her husband. But it’s not that simple. Most women with children who leave are forced to give up custody of their kids and see them rarely, if at all. It’s what happened when Feldman’s own mother left and why she barely knew the woman who bore her before she left the Satmar community herself.

Feldman’s story has none of the warm fuzziness of sisterhood that Levine’s does. There were moments of happiness for her, but most of them involved reading things she was not supposed to be reading. Granted, Satmar is one of the strictest Hasidic sects. Women don’t drive, and even learning is frowned upon. If Feldman was caught in a public library or with an English language book she’d get a tongue lashing from her elders. Speaking English was a no-no. Singing for women forbidden. Among the Satmar there is little room for joy — particularly for women — and beauty and modernity.

I remain curious. These two tales can’t be the only ones to be told. I actually have a new friend who is part of the Lubavitcher world — she runs the Friendship Circle of Washington about which I wrote two days ago. I have a list of questions I want to ask her about how she was raised and the life she chose. But she’s a busy lady — a job, a handful of children ranging from baby to teen, a home and husband to take care of. I bet she doesn’t feel imprisoned or restrained by her life. But I also wonder if any of her children will feel restricted and will want more freedom than life in a sect that is run by the rules of the 19th century allows. And I wonder what she’ll do if they opt to pursue it.

I have never been able to understand why women put up with restrictive religious practices in any sect or religion, and then I remind myself that often that is all they know. When restrictions are put on people to control them, their education, their life choices, their dreams of course we all know that it is fear that drives that control. That makes me completely sad as a large part of the joy in life is taken away also.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts on these two books. I grew up in a mildly restrictive (compared to say, Amish or Hasidic Judaism) evangelical home. I knew girls (and boys) from far more restrictive homes. I think the thing that distresses me is not that these communities exist and many within in seem to be very happy with their lives but that the community punishes and ejects those who chose something else. If the community trusts that most will choose it and be happy, why reject those who do not?

That’s a really good point. I often think the same kind of thing about repressive governments: if you’re so sure you are loved, why not let people talk about you, write about you, or leave the country? And I think, too, that a lot of what happens to the individual who wants something different depends on his or her family.